Arthritis of the Foot and Ankle

Arthritis is inflammation of one or more of your joints. It can cause pain and stiffness in any joint in the body, and is common in the small joints of the foot and ankle.

There are more than 100 forms of arthritis, many of which affect the foot and ankle. All types can make it difficult to walk and perform activities you enjoy.

Although there is no cure for arthritis, there are many treatment options available to slow the progress of the disease and relieve symptoms. With proper treatment, many people with arthritis are able to manage their pain, remain active, and lead fulfilling lives.

Anatomy

During standing, walking, and running, the foot and ankle provide support, shock absorption, balance, and several other functions that are essential for motion. Three bones make up the ankle joint, primarily enabling up and down movement. There are 28 bones in the foot, and more than 30 joints that allow for a wide range of movement.

During standing, walking, and running, the foot and ankle provide support, shock absorption, balance, and several other functions that are essential for motion. Three bones make up the ankle joint, primarily enabling up and down movement. There are 28 bones in the foot, and more than 30 joints that allow for a wide range of movement.

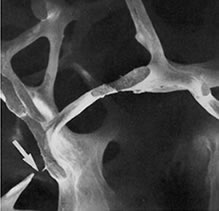

In many of these joints the ends of the bones are covered with articular cartilage—a slippery substance that helps the bones glide smoothly over each other during movement. Joints are surrounded by a thin lining called the synovium. The synovium produces a fluid that lubricates the cartilage and reduces friction.

Tough bands of tissue, called ligaments, connect the bones and keep the joints in place. Muscles and tendons also support the joints and provide the strength to make them move.

Description

The major types of arthritis that affect the foot and ankle are osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and posttraumatic arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative or “wear-and-tear” arthritis, is a common problem for many people after they reach middle age, but it may occur in younger people, too.

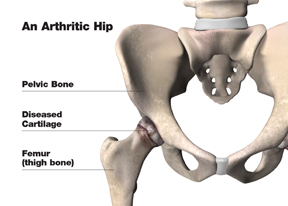

In osteoarthritis, the cartilage in the joint gradually wears away. As the cartilage wears away, it becomes frayed and rough, and the protective space between the bones decreases. This can result in bone rubbing on bone, and produce painful osteophytes (bone spurs).

In addition to age, other risk factors for osteoarthritis include obesity and family history of the disease.

Osteoarthritis develops slowly, causing pain and stiffness that worsen over time.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic disease that can affect multiple joints throughout the body, and often starts in the foot and ankle. It is symmetrical, meaning that it usually affects the same joint on both sides of the body.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic disease that can affect multiple joints throughout the body, and often starts in the foot and ankle. It is symmetrical, meaning that it usually affects the same joint on both sides of the body.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system attacks its own tissues. In rheumatoid arthritis, immune cells attack the synovium covering the joint, causing it to swell. Over time, the synovium invades and damages the bone and cartilage, as well as ligaments and tendons, and may cause serious joint deformity and disability.

The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not known. Although it is not an inherited disease, researchers believe that some people have genes that make them more susceptible. There is usually a “trigger,” such as an infection or environmental factor, which activates the genes. When the body is exposed to this trigger, the immune system begins to produce substances that attack the joints.

Posttraumatic Arthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis can develop after an injury to the foot or ankle. Dislocations and fractures—particularly those that damage the joint surface—are the most common injuries that lead to posttraumatic arthritis. Like osteoarthritis, posttraumatic arthritis causes the cartilage between the joints to wear away. It can develop many years after the initial injury.

An injured joint is about seven times more likely than an uninjured joint to become arthritic, even if the injury is properly treated. In fact, following an injury, your body may actually secrete hormones that stimulate the death of your cartilage cells.

Symptoms

The symptoms of arthritis vary depending on which joint is affected. In many cases, an arthritic joint will be painful and inflamed. Generally, the pain develops gradually over time, although sudden onset is also possible. There can be other symptoms, as well, including:

- Pain with motion

- Pain that flares up with vigorous activity

- Tenderness when pressure is applied to the joint

- Joint swelling, warmth, and redness

- Increased pain and swelling in the morning, or after sitting or resting

- Difficulty in walking due to any of the above symptoms

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will discuss your overall health and medical history and ask about any medications you may be taking. He or she will examine your foot and ankle for tenderness and swelling and ask questions to understand more about your symptoms. These questions may include:

- When did the pain start?

- Where exactly is the pain? Does it occur in one foot or in both feet?

- When does the pain occur? Is it continuous, or does it come and go?

- Is the pain worse in the morning or at night? Does it get worse when walking or running?

Your doctor will also ask if you have had an injury to your foot or ankle in the past. If so, he or she will discuss your injury, including when it occurred and how it was treated.

Your doctor will also examine your shoes to determine if there is any abnormal or uneven wear and to ensure that they are providing sufficient support for your foot and ankle.

Gait analysis. During the physical examination, your doctor will closely observe your gait (the way you walk). Pain and joint stiffness will change the way you walk. For example, if you are limping, the way you limp can tell your doctor a lot about the severity and location of your arthritis.

During the gait analysis, your doctor will assess how the bones in your leg and foot line up when you walk, measure your stride, and test the strength of your ankles and feet.

Tests

X-rays. These imaging tests provide detailed pictures of dense structures such as bone. An x-ray of an arthritic foot may show narrowing of the joint space between bones (an indication of cartilage loss), changes in the bone (such as fractures), or the formation of bone spurs.

Weight-bearing x-rays are taken while you stand. They are the most valuable additional test in diagnosing the severity of arthritis and noting any joint deformity associated with it. In arthritic conditions, if x-rays are taken without standing, it is difficult to assess how much arthritis is present, where it is located in the joint, and how much deformity is present. So, it is very important that, when possible, x-rays are taken standing.

Other imaging tests. In some cases, a bone scan, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be needed to determine the condition of the bone and soft tissues.

Laboratory tests. Your doctor may also recommend blood tests to determine which type of arthritis you have. With some types of arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis, blood tests are important for an accurate diagnosis.

Your doctor may refer you to a rheumatologist if he or she suspects rheumatoid arthritis. Although your symptoms and the results from a physical examination and tests may be consistent with rheumatoid arthritis, a rheumatologist will be able to determine the specific diagnosis. There are other less common types of inflammatory arthritis that will be considered.

Treatment

There is no cure for arthritis but there are a number of treatments that may help relieve the pain and disability it can cause.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Initial treatment of arthritis of the foot and ankle is usually nonsurgical. Your doctor may recommend a range of treatment options.

Lifestyle modifications. Some changes in your daily life can help relieve the pain of arthritis and slow the progression of the disease. These changes include:

- Minimizing activities that aggravate the condition.

- Switching from high-impact activities (like jogging or tennis) to lower impact activities (like swimming or cycling) to lessen the stress on your foot and ankle.

- Losing weight to reduce stress on the joints, resulting in less pain and increased function.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help increase range of motion and flexibility, as well as help strengthen the muscles in your foot and ankle. Your doctor or a physical therapist can help develop an individualized exercise program that meets your needs and lifestyle.

Although physical therapy often helps relieve stress on the arthritic joints, in some cases it may intensify joint pain. This occurs when movement creates increasing friction between the arthritic joints. If your joint pain is aggravated by physical therapy, your doctor will stop this form of treatment.

Assistive devices. Using a cane or wearing a brace—such as an ankle-foot orthosis (AFO)-may help improve mobility. In addition, wearing shoe inserts (orthotics) or custom-made shoes with stiff soles and rocker bottoms can help minimize pressure on the foot and decrease pain. In addition, if deformity is present, a shoe insert may tilt the foot of ankle back straight, creating less pain in the joint.

Medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and naproxen, can help reduce swelling and relieve pain. In addition, cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory agent that can be injected into an arthritic joint. Although an injection of cortisone can provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, the effects are temporary.

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain causes disability and is not relieved with nonsurgical treatment. The type of surgery will depend on the type and location of the arthritis and the impact of the disease on your joints. In some cases, your doctor may recommend more than one type of surgery.

Arthroscopic debridement. This surgery may be helpful in the early stages of arthritis. Debridement (cleansing) is a procedure to remove loose cartilage, inflamed synovial tissue, and bone spurs from around the joint.

During arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your foot or ankle joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, your surgeon can use very small incisions (cuts), rather than the larger incision needed for a traditional, open surgery.

During arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your foot or ankle joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, your surgeon can use very small incisions (cuts), rather than the larger incision needed for a traditional, open surgery.

Arthroscopic surgery is most effective when pain is due to contact between bone spurs and the arthritis has not yet caused significant narrowing of the joint space between the bones. Arthroscopy can make an arthritic joint deteriorate more rapidly. Removing bone spurs may increase motion in the joint, causing the cartilage to wear away quicker.

Arthrodesis (fusion). Arthrodesis fuses the bones of the joint completely, making one continuous bone out of two or more bones. The goal of the procedure is to reduce pain by eliminating motion in the arthritic joint.

During arthrodesis, the doctor removes the damaged cartilage and then uses pins, plates and screws, or rods to fix the joint in a permanent position. Over time, the bones fuse or grow together, just like two ends of a broken bone grow together as it heals. By removing the joint, the pain disappears.

During arthrodesis, the doctor removes the damaged cartilage and then uses pins, plates and screws, or rods to fix the joint in a permanent position. Over time, the bones fuse or grow together, just like two ends of a broken bone grow together as it heals. By removing the joint, the pain disappears.

Arthrodesis is typically quite successful, although there can be complications. In some cases, the joint does not fuse together (nonunion), and the hardware may break. This may happen if you put weight on your foot before the fusion is complete. While the broken hardware does not cause pain, the nonunion of the fusion can lead to pain and swelling. If nonunion occurs, a second operation to place bone graft in the ankle and place new hardware may be needed. However, repeated fusions are not as likely to be successful, so it is best to closely follow your doctor’s guidelines during the recovery period of your original operation.

A small percentage of patients have problems with wound healing, but these problems can usually be addressed by bracing or by an additional surgery. In some cases, loss of motion in the ankle after a fusion causes the joints adjacent to the one fused to bear more stress than they did before the surgery. This can lead to arthritis in the adjacent joints years after the surgery.

A small percentage of patients have problems with wound healing, but these problems can usually be addressed by bracing or by an additional surgery. In some cases, loss of motion in the ankle after a fusion causes the joints adjacent to the one fused to bear more stress than they did before the surgery. This can lead to arthritis in the adjacent joints years after the surgery.

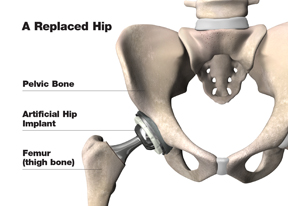

Total ankle replacement (arthroplasty). In total ankle replacement, your doctor removes the damaged cartilage and bone, and then positions new metal or plastic joint surfaces to restore the function of the joint.

Although total ankle replacement is not as common as total hip or total knee replacement, advances in implant design have made it a viable option for many people.

Ankle replacement is most often recommended for patients who have:

- Advanced arthritis of the ankle

- Arthritis that has destroyed the ankle joint surfaces

- Ankle pain that interferes with daily activities

Ankle replacement relieves the pain of arthritis and offers patients more mobility and movement than fusion. In addition, being able to move the formerly arthritic joint means that less stress is transferred to the adjacent joints. This lessens the chance of developing adjacent joint arthritis.

As in any type of joint replacement, an ankle implant may loosen or fail over the years. If the implant failure is severe, the replaced joint can be exchanged for a new implant — this procedure is called a revision surgery.

Another option is to remove the implant and fuse the joint. This type of fusion is more difficult than when fusion is done as the initial procedure. When the implant is removed, there is space in the bone that must be filled with bone graft to maintain the length of the leg. Because the new bone may not be as strong, the risk of nonunion is greater.

Recovery

In most cases, surgery relieves the pain of arthritis and makes it easier to perform daily activities. Full recovery can take from 4 to 9 months, depending on the severity of your condition before surgery and the complexity of your procedure.

Foot and ankle surgery can be painful. While you should expect to feel some discomfort, advancements in pain control now make it easier for your doctor to manage and relieve pain. Immediately after surgery, you will be given medication for pain relief. If needed, your doctor will provide you with a pain reliever that you can take for a short time while you are home.

Your doctor will most likely apply a cast after surgery to limit movement in your foot and ankle and to prevent nonunion. To reduce swelling, it is important to keep your foot elevated above the level of your heart for 1 to 2 weeks after surgery.

Later in your recovery, your doctor may recommend physical therapy to help you regain strength in your foot or ankle and to restore range of motion.

In most cases, you will be able to resume your daily activities in 3 to 4 months although, for a period of time, you may need to wear supportive shoes or a brace.

Total hip replacement (also known as hip arthroplasty) is a common orthopaedic procedure and, as the population ages, it is expected to become even more common. Replacing the hip joint with an implant or “prosthesis” relieves pain and improves mobility so that you are able to resume your normal, everyday activities.

The traditional surgical approach to total hip replacement uses a single, long incision to view and access the hip joint. A variation of this approach is a minimally invasive procedure in which one or two shorter incisions are used. The goal of using shorter incisions is to reduce pain and speed recovery. Unlike traditional total hip replacement, the minimally invasive technique is not suitable for all patients. Your orthopaedic surgeon will discuss different surgical options with you.

Description

During any hip replacement surgery, the damaged bone is cut and removed, along with some soft tissues. In minimally invasive surgery, a smaller surgical incision is used and fewer muscles around the hip are cut or detached. Despite this difference, however, both traditional hip replacement surgery and minimally invasive surgery are technically demanding and have better outcomes if the surgeon and operating team have considerable experience.

Traditional Hip Replacement

To perform a traditional hip replacement:

- A 10- to 12-inch incision is made on the side of the hip. The muscles are split or detached from the hip, allowing the hip to be dislocated and fully viewed by the surgical team.

- The damaged femoral head is removed and replaced with a metal stem that is placed into the hollow center of the femur, then a metal or ceramic ball is placed on the upper part of the stem. This ball replaces the damaged femoral head that was removed.

- The damaged cartilage surface of the socket (acetabulum) is removed and replaced with a metal socket. Screws or cement are sometimes used to hold the socket in place.

- A plastic, ceramic or metal spacer is inserted between the new ball and the socket to allow for a smooth gliding surface.

Minimally Invasive Hip Replacement

In minimally invasive total hip replacement, the surgical procedure is similar, but there is less cutting of the tissue surrounding the hip. The artificial implants used are the same as those used for traditional hip replacement. However, specially designed surgical instruments are needed to prepare the socket and femur and to place the implants properly.

Minimally invasive total hip replacement can be performed with either one or two small incisions. Smaller incisions allow for less tissue disturbance.

- Single-incision surgery. In this type of minimally invasive hip replacement, the surgeon makes a single incision that usually measures from 3 to 6 inches. The length of the incision depends on the size of the patient and the difficulty of the procedure.

The incision is usually placed over the outside of the hip. The muscles and tendons are split or detached from the hip, but to a lesser extent than in traditional hip replacement surgery. They are routinely repaired after the surgeon places the implants. This encourages healing and helps prevent dislocation of the hip.

- Two-incision surgery. In this type of minimally invasive hip replacement, the surgeon makes two small incisions:

- A 2- to 3-inch incision over the groin for placement of the socket, and

- A 1- to 2-inch incision over the buttock for placement of the femoral stem.

To perform the two-incision procedure, the surgeon may need guidance from x-rays. It may take longer to perform the two-incision surgery than it does to perform traditional hip replacement surgery.

The hospital stay after minimally invasive surgery is similar in length to the stay after traditional hip replacement surgery–ranging from 1 to 4 days. Physical rehabilitation is a critical component of recovery. Your surgeon or a physical therapist will provide you with specific exercises to help increase your range of motion and restore your strength.

Candidates for Minimally Invasive Total Hip Replacement

Minimally invasive total hip replacement is not suitable for all patients. Your doctor will conduct a comprehensive evaluation and consider several factors before determining if the procedure is an option for you.

In general, candidates for minimal incision procedures are thinner, younger, healthier, and more motivated to participate in the rehabilitation process, compared with patients who undergo the traditional surgery.

Minimally invasive techniques are less suitable for patients who are overweight or who have already undergone other hip surgeries. In addition, patients who have a significant deformity of the hip joint, those who are very muscular, and those with health problems that may slow wound healing may be at a higher risk for problems from minimally invasive total hip replacement.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive and small incision total hip replacement surgery is an evolving area and more research is needed on the long-term function and durability of the implants.

The benefits of minimally invasive hip replacement have been reported to include less damage to soft tissues, leading to a quicker, less painful recovery and more rapid return to normal activities. Current evidence suggests that the long-term benefits of minimally invasive surgery do not differ from those of hip replacement performed with the traditional approach.

Like all surgery, minimally invasive surgery has a risk of complications. These complications include nerve and artery injuries, wound healing problems, infection, fracture of the femur, and errors in positioning the prosthetic hip implants.

Like traditional hip replacement surgery, minimally invasive surgery should be performed by a well-trained, highly experienced orthopaedic surgeon. Your orthopaedic surgeon can talk to you about his or her experience with minimally invasive hip replacement surgery, and the possible risks and benefits of the techniques for your individual treatment.

There are more than 100 different forms of arthritis, a disease that can make it difficult to do everyday activities because of joint pain and stiffness.

Inflammatory arthritis occurs when the body’s immune system becomes overactive and attacks healthy tissues. It can affect several joints throughout the body at the same time, as well as many organs, such as the skin, eyes, and heart.

There are three types of inflammatory arthritis that most often cause symptoms in the hip joint:

- Rheumatoid arthritis;

- Ankylosing spondylitis; and

- Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Although there is no cure for inflammatory arthritis, there have been many advances in treatment, particularly in the development of new medications. Early diagnosis and treatment can help patients maintain mobility and function by preventing severe damage to the joint.

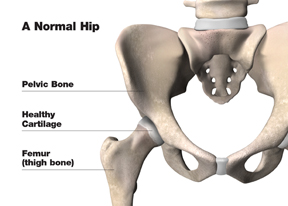

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and socket. It creates a smooth, low-friction surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other. The surface of the joint is covered by a thin lining called the synovium. In a healthy hip, the synovium produces a small amount of fluid that lubricates the cartilage and aids in movement.

Description

The most common form of arthritis in the hip is osteoarthritis — the “wear-and-tear” arthritis that damages cartilage over time, typically causing painful symptoms in people after they reach middle age. Unlike osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis affects people of all ages, often showing signs in early adulthood.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

In rheumatoid arthritis, the synovium thickens, swells, and produces chemical substances that attack and destroy the articular cartilage covering the bone. Rheumatoid arthritis often involves the same joint on both sides of the body, so both hips may be affected.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammation of the spine that most often causes lower back pain and stiffness. It may affect other joints, as well, including the hip.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause inflammation in any part of the body, and most often affects the joints, skin, and nervous system. The disease occurs in young adult women in the majority of cases.

People with systemic lupus erythematosus have a higher incidence of osteonecrosis of the hip, a disease that causes bone cells to die, weakens bone structure, and leads to disabling arthritis.

Cause

The exact cause of inflammatory arthritis is not known, although there is evidence that genetics plays a role in the development of some forms of the disease.

Symptoms

Inflammatory arthritis may cause general symptoms throughout the body, such as fever, loss of appetite and fatigue. A hip affected by inflammatory arthritis will feel painful and stiff. There are other symptoms, as well:

- A dull, aching pain in the groin, outer thigh, knee, or buttocks

- Pain that is worse in the morning or after sitting or resting for a while, but lessens with activity

- Increased pain and stiffness with vigorous activity

- Pain in the joint severe enough to cause a limp or make walking difficult

Doctor Examination

Your doctor will ask questions about your medical history and your symptoms, then conduct a physical examination and order diagnostic tests.

Physical Examination

During the physical examination, your doctor will evaluate the range of motion in your hip. Increased pain during some movements may be a sign of inflammatory arthritis. He or she will also look for a limp or other problems with your gait (the way you walk) due to stiffness of the hip.

X-rays

X-rays are imaging tests that create detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. X-rays of an arthritic hip will show whether there is any thinning or erosion in the bones, any loss of joint space, or any excess fluid in the joint.

Blood Tests

Blood tests may reveal whether a rheumatoid factor—or any other antibody indicative of inflammatory arthritis—is present.

Treatment

Although there is no cure for inflammatory arthritis, there are a number of treatment options that can help prevent joint destruction. Inflammatory arthritis is often treated by a team of healthcare professionals, including rheumatologists, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and orthopaedic surgeons.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The treatment plan for managing your symptoms will depend upon your inflammatory disease. Most people find that some combination of treatment methods works best.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drugs like naproxen and ibuprofen may relieve pain and help reduce inflammation. NSAIDs are available in both over-the-counter and prescription forms.

Corticosteroids. Medications like prednisone are potent anti-inflammatories. They can be taken by mouth, by injection, or used as creams that are applied directly to the skin.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs act on the immune system to help slow the progression of disease. Methotrexate and sulfasalazine are commonly prescribed DMARDs.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises may help increase the range of motion in your hip and strengthen the muscles that support the joint.

In addition, regular, moderate exercise may decrease stiffness and improve endurance. Swimming is a preferred exercise for people with ankylosing spondylitis because spinal motion may be limited.

Assistive devices. Using a cane, walker, long-handled shoehorn, or reacher may make it easier for you to perform the tasks of daily living.

Surgical Treatment

If nonsurgical treatments do not sufficiently relieve your pain, your doctor may recommend surgery. The type of surgery performed depends on several factors, including:

- Your age

- Condition of the hip joint

- Which disease is causing your inflammatory arthritis

- Progression of the disease

The most common surgical procedures performed for inflammatory arthritis of the hip include total hip replacement and synovectomy.

Total hip replacement. Your doctor will remove the damaged cartilage and bone, and then position new metal or plastic joint surfaces to restore the function of your hip. Total hip replacement is often recommended for patients with rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis to relieve pain and improve range of motion.

Synovectomy. Synovectomy is done to remove part or all of the joint lining (synovium). It may be effective if the disease is limited to the joint lining and has not affected the articular cartilage that covers the bones. Generally, the procedure is used to treat only the early stages of inflammatory arthritis.

Your doctor will discuss the various surgical options with you. Do not hesitate to ask why a specific procedure is being recommended and what outcome you can expect.

Complications. Although complications are possible in any surgery, your doctor will take steps to minimize the risks. The most common complications of surgery include:

- Infection

- Excessive bleeding

- Blood clots

- Damage to blood vessels or arteries

- Dislocation (in total hip replacement)

- Limb length inequality (in total hip replacement)

Your doctor will discuss all the possible complications with you before your surgery.

Recovery. How long it takes to recover and resume your daily activities will depend on several factors, including your general health and the type of surgical procedure you have. Initially, you may need a cane, walker, or crutches to walk. Your doctor may recommend physical therapy to help you regain strength in your hip and to restore range of motion.

Outcomes

Inflammatory arthritis of the hip can cause a wide range of disabling symptoms. Today, new medications may prevent progression of disease and joint destruction. Early treatment can help preserve the hip joint.

In cases that progress to severe joint damage, surgery can relieve your pain, increase motion, and help you get back to enjoying everyday activities. Total hip replacement is one of the most successful operations in all of medicine.

A hip strain occurs when one of the muscles supporting the hip joint is stretched beyond its limit or torn. Strains may be mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the extent of the injury. A severe strain can limit your ability to move your hip.

Anyone can experience a hip strain just doing everyday tasks, but strains most often occur during sports activities.

Although many hip strains improve with simple home treatment, severe strains may require physical therapy or other medical treatment.

Description

The large bones that make up the hip joint—the femur (thighbone) and the pelvis—serve as anchors for several muscles. Some of these muscles move across the abdomen or the buttocks (hip flexors, gluteals). Others move down the thigh to the knee (abductors, adductors, quadriceps, hamstrings).

In a hip strain, muscles and tendons may be injured. Tendons are the tough, fibrous tissues that connect muscles to bones. Hip strains frequently occur near the point where the muscle joins the connective tissue of the tendon.

The strain may be a simple stretch in your muscle or tendon, or it may be a partial or complete tear of muscle fibers or of the muscle and tendon combination.

Once the muscle is injured, it becomes vulnerable to reinjury. Repeated strains in muscles about the hip and pelvis may be associated with athletic pubalgia (also called sports hernia). A sports hernia is a strain or tear of any soft tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament) in the lower abdomen or groin area. This condition is discussed in Sports Hernia (Athletic Pubalgia).

Cause

A hip strain can be an acute injury—meaning that it occurs suddenly, such as from a fall or a direct blow during contact sports. Hip strains are also caused by overuse—when the muscle or tendon has slowly become weakened over time by repetitive movements.

Factors that put you at greater risk for a hip strain include:

- Prior injury in the same area

- Muscle tightness

- Failure to warm up properly before exercising

- Attempting to do too much, too quickly, when you exercise

Symptoms

A muscle strain causes pain and tenderness in the injured area. Other symptoms may include:

- Increased pain when you use the muscle

- Swelling

- Limited range of motion

- Muscle weakness

Home Remedies

Many hip strains will improve with simple home treatment. Mild strains can be treated with the RICE protocol. RICE stands for rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

- Rest. Avoid activities that put weight on the hip for the first few days after the injury.

- Ice. Apply ice immediately after the injury to keep the swelling down. Use cold packs for 20 minutes at a time, several times a day. Do not apply ice directly on the skin.

- Compression. To prevent additional swelling, lightly wrap the area in a soft bandage or wear compression shorts.

- Elevation. As often as possible, rest with your leg raised up higher than your heart.

In addition, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, can help reduce swelling and relieve pain.

If the pain persists or it becomes more difficult to move your hip and leg, contact your doctor.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will discuss your general health and ask you about what activities you were doing just prior to the injury. He or she will examine your leg and hip for tenderness or swelling. During the physical examination, your doctor will apply pressure to various muscles in the area and move your leg and hip in various directions to assess your range of motion.

Your doctor may also ask you to perform a variety of stretches and movements to help determine which muscle is injured.

X-Rays

X-rays provide images of dense structures such as bone. Your doctor may order an x-ray to rule out the possibility of a stress fracture of the hip, which has similar symptoms. In most cases, no additional imaging tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Medical treatment for muscle strains is designed to relieve pain and restore range of motion and strength. The majority of hip strains are treated nonsurgically.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In addition to the RICE method and anti-inflammatory medication, your doctor may recommend using crutches for a few days to limit the weight on your hip. Other recommendations may include:

- Heat therapy. Ice should be applied immediately after an acute injury to reduce swelling. After 72 hours, however, alternating ice with heat therapy—which may include soaking in a hot bath or using a heat lamp or heating pad—may help relieve pain and improve range of motion.

- Home exercise program. Specific exercises can strengthen the muscles that support the hip and help to improve muscle endurance and flexibility.

- Physical therapy. If pain persists after a few weeks of home exercise, your doctor may recommend formal physical rehabilitation. A physical therapist can provide an individualized exercise program to improve strength and flexibility.

Surgical Treatment

Severe injuries in which the muscle fibers are completely torn may require surgery in order to return to normal function and movement. Surgery typically involves stitching the torn pieces back together.

Many severe hip strains are successfully treated without surgery. Your doctor will discuss the treatment options that best meet your individual health needs.

Recovery

In most cases, you should avoid the activity that caused your injury for 10 to14 days. A severe muscle strain may require a longer period of recovery. If your pain returns when you resume more strenuous activity, however, discontinue what you are doing and go back to easier activities that do not cause pain.

You can take the following precautions to help prevent muscle strains in the future:

- Condition your muscles with a regular program of exercise. Ask your doctor about exercise programs for people of your age and activity level.

- Warm up before any exercise session or sports activity, including practice. A good warm up prepares your body for more intense activity. It gets your blood flowing, raises your muscle temperature, and increases your breathing rate. Warming up gives your body time to adjust to the demands of exercise. It increases your range of motion and reduces stiffness.

- Wear or use appropriate protective gear for your sport.

- Take time to cool down after exercise. Instead of performing a large number of rapid stretches, stretch slowly and gradually, holding each stretch to give your muscle time to respond and lengthen. You can find examples of stretching exercises in the Related Resources section of this article or ask your doctor or coach for help in developing a routine.

- Take the time needed to let your muscle heal before you return to sports. Wait until your muscle strength and flexibility return to preinjury levels.

Total Hip Replacement

Information on total hip replacement is also available in Spanish: Reemplazo total de cadera and Portuguese: Artroplastia total de quadril.

Whether you have just begun exploring treatment options or have already decided to undergo hip replacement surgery, this information will help you understand the benefits and limitations of total hip replacement. This article describes how a normal hip works, the causes of hip pain, what to expect from hip replacement surgery, and what exercises and activities will help restore your mobility and strength, and enable you to return to everyday activities.

If your hip has been damaged by arthritis, a fracture, or other conditions, common activities such as walking or getting in and out of a chair may be painful and difficult. Your hip may be stiff, and it may be hard to put on your shoes and socks. You may even feel uncomfortable while resting.

If medications, changes in your everyday activities, and the use of walking supports do not adequately help your symptoms, you may consider hip replacement surgery. Hip replacement surgery is a safe and effective procedure that can relieve your pain, increase motion, and help you get back to enjoying normal, everyday activities.

First performed in 1960, hip replacement surgery is one of the most successful operations in all of medicine. Since 1960, improvements in joint replacement surgical techniques and technology have greatly increased the effectiveness of total hip replacement. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, more than 300,000 total hip replacements are performed each year in the United States.

Anatomy

The hip is one of the body’s largest joints. It is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

The bone surfaces of the ball and socket are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth tissue that cushions the ends of the bones and enables them to move easily.

A thin tissue called synovial membrane surrounds the hip joint. In a healthy hip, this membrane makes a small amount of fluid that lubricates the cartilage and eliminates almost all friction during hip movement.

Bands of tissue called ligaments (the hip capsule) connect the ball to the socket and provide stability to the joint.

Common Causes of Hip Pain

The most common cause of chronic hip pain and disability is arthritis. Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and traumatic arthritis are the most common forms of this disease.

- Osteoarthritis. This is an age-related “wear and tear” type of arthritis. It usually occurs in people 50 years of age and older and often in individuals with a family history of arthritis. The cartilage cushioning the bones of the hip wears away. The bones then rub against each other, causing hip pain and stiffness. Osteoarthritis may also be caused or accelerated by subtle irregularities in how the hip developed in childhood.

- Rheumatoid arthritis. This is an autoimmune disease in which the synovial membrane becomes inflamed and thickened. This chronic inflammation can damage the cartilage, leading to pain and stiffness. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common type of a group of disorders termed “inflammatory arthritis.”

- Post-traumatic arthritis. This can follow a serious hip injury or fracture. The cartilage may become damaged and lead to hip pain and stiffness over time.

- Avascular necrosis. An injury to the hip, such as a dislocation or fracture, may limit the blood supply to the femoral head. This is called avascular necrosis (also commonly referred to as “osteonecrosis”). The lack of blood may cause the surface of the bone to collapse, and arthritis will result. Some diseases can also cause avascular necrosis.

- Childhood hip disease. Some infants and children have hip problems. Even though the problems are successfully treated during childhood, they may still cause arthritis later on in life. This happens because the hip may not grow normally, and the joint surfaces are affected.

Animation courtesy Visual Health Solutions, Inc.

Description

In a total hip replacement (also called total hip arthroplasty), the damaged bone and cartilage is removed and replaced with prosthetic components.

- The damaged femoral head is removed and replaced with a metal stem that is placed into the hollow center of the femur. The femoral stem may be either cemented or “press fit” into the bone.

- A metal or ceramic ball is placed on the upper part of the stem. This ball replaces the damaged femoral head that was removed.

- The damaged cartilage surface of the socket (acetabulum) is removed and replaced with a metal socket. Screws or cement are sometimes used to hold the socket in place.

- A plastic, ceramic, or metal spacer is inserted between the new ball and the socket to allow for a smooth gliding surface.

Animation courtesy Visual Health Solutions, Inc.

Is Hip Replacement Surgery for You?

The decision to have hip replacement surgery should be a cooperative one made by you, your family, your primary care doctor, and your orthopaedic surgeon. The process of making this decision typically begins with a referral by your doctor to an orthopaedic surgeon for an initial evaluation.

Candidates for Surgery

There are no absolute age or weight restrictions for total hip replacements.

Recommendations for surgery are based on a patient’s pain and disability, not age. Most patients who undergo total hip replacement are age 50 to 80, but orthopaedic surgeons evaluate patients individually. Total hip replacements have been performed successfully at all ages, from the young teenager with juvenile arthritis to the elderly patient with degenerative arthritis.

When Surgery Is Recommended

There are several reasons why your doctor may recommend hip replacement surgery. People who benefit from hip replacement surgery often have:

- Hip pain that limits everyday activities, such as walking or bending

- Hip pain that continues while resting, either day or night

- Stiffness in a hip that limits the ability to move or lift the leg

- Inadequate pain relief from anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, or walking supports

The Orthopaedic Evaluation

An evaluation with an orthopaedic surgeon consists of several components.

- Medical history. Your orthopaedic surgeon will gather information about your general health and ask questions about the extent of your hip pain and how it affects your ability to perform everyday activities.

- Physical examination. This will assess hip mobility, strength, and alignment.

- X-rays. These images help to determine the extent of damage or deformity in your hip.

- Other tests. Occasionally other tests, such as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, may be needed to determine the condition of the bone and soft tissues of your hip.

Deciding to Have Hip Replacement Surgery

Talk With Your Doctor

Your orthopaedic surgeon will review the results of your evaluation with you and discuss whether hip replacement surgery is the best method to relieve your pain and improve your mobility. Other treatment options — such as medications, physical therapy, or other types of surgery — also may be considered.

In addition, your orthopaedic surgeon will explain the potential risks and complications of hip replacement surgery, including those related to the surgery itself and those that can occur over time after your surgery.

Never hesitate to ask your doctor questions when you do not understand. The more you know, the better you will be able to manage the changes that hip replacement surgery will make in your life.

Realistic Expectations

An important factor in deciding whether to have hip replacement surgery is understanding what the procedure can and cannot do. Most people who undergo hip replacement surgery experience a dramatic reduction of hip pain and a significant improvement in their ability to perform the common activities of daily living.

With normal use and activity, the material between the head and the socket of every hip replacement implant begins to wear. Excessive activity or being overweight may speed up this normal wear and cause the hip replacement to loosen and become painful. Therefore, most surgeons advise against high-impact activities such as running, jogging, jumping, or other high-impact sports.

Realistic activities following total hip replacement include unlimited walking, swimming, golf, driving, hiking, biking, dancing, and other low-impact sports.

With appropriate activity modification, hip replacements can last for many years.

Preparing for Surgery

Medical Evaluation

If you decide to have hip replacement surgery, your orthopaedic surgeon may ask you to have a complete physical examination by your primary care doctor before your surgical procedure. This is needed to make sure you are healthy enough to have the surgery and complete the recovery process. Many patients with chronic medical conditions, like heart disease, may also be evaluated by a specialist, such a cardiologist, before the surgery.

Tests

Several tests, such as blood and urine samples, an electrocardiogram (EKG), and chest x-rays, may be needed to help plan your surgery.

Preparing Your Skin

Your skin should not have any infections or irritations before surgery. If either is present, contact your orthopaedic surgeon for treatment to improve your skin before surgery.

Blood Donations

You may be advised to donate your own blood prior to surgery. It will be stored in the event you need blood after surgery.

Medications

Tell your orthopaedic surgeon about the medications you are taking. He or she or your primary care doctor will advise you which medications you should stop taking and which you can continue to take before surgery.

Weight Loss

If you are overweight, your doctor may ask you to lose some weight before surgery to minimize the stress on your new hip and possibly decrease the risks of surgery.

Dental Evaluation

Although infections after hip replacement are not common, an infection can occur if bacteria enter your bloodstream. Because bacteria can enter the bloodstream during dental procedures, major dental procedures (such as tooth extractions and periodontal work) should be completed before your hip replacement surgery. Routine cleaning of your teeth should be delayed for several weeks after surgery.

Urinary Evaluation

Individuals with a history of recent or frequent urinary infections should have a urological evaluation before surgery. Older men with prostate disease should consider completing required treatment before having surgery.

Social Planning

Although you will be able to walk with crutches or a walker soon after surgery, you will need some help for several weeks with such tasks as cooking, shopping, bathing, and laundry.

If you live alone, your orthopaedic surgeon’s office, a social worker, or a discharge planner at the hospital can help you make advance arrangements to have someone assist you at your home. A short stay in an extended care facility during your recovery after surgery also may be arranged.

Home Planning

Several modifications can make your home easier to navigate during your recovery. The following items may help with daily activities:

- Securely fastened safety bars or handrails in your shower or bath

- Secure handrails along all stairways

- A stable chair for your early recovery with a firm seat cushion (that allows your knees to remain lower than your hips), a firm back, and two arms

- A raised toilet seat

- A stable shower bench or chair for bathing

- A long-handled sponge and shower hose

- A dressing stick, a sock aid, and a long-handled shoe horn for putting on and taking off shoes and socks without excessively bending your new hip

- A reacher that will allow you to grab objects without excessive bending of your hips

- Firm pillows for your chairs, sofas, and car that enable you to sit with your knees lower than your hips

- Removal of all loose carpets and electrical cords from the areas where you walk in your home

![fig40 [Converted]](http://st9.idsil.com/dev/doctors/dukeahn/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2016/12/hip-implants-img6.jpg)

Your Surgery

You will most likely be admitted to the hospital on the day of your surgery.

Anesthesia

After admission, you will be evaluated by a member of the anesthesia team. The most common types of anesthesia are general anesthesia (you are put to sleep) or spinal, epidural, or regional nerve block anesthesia (you are awake but your body is numb from the waist down). The anesthesia team, with your input, will determine which type of anesthesia will be best for you.

Implant Components

Many different types of designs and materials are currently used in artificial hip joints. All of them consist of two basic components: the ball component (made of highly polished strong metal or ceramic material) and the socket component (a durable cup of plastic, ceramic or metal, which may have an outer metal shell).

The prosthetic components may be “press fit” into the bone to allow your bone to grow onto the components or they may be cemented into place. The decision to press fit or to cement the components is based on a number of factors, such as the quality and strength of your bone. A combination of a cemented stem and a non-cemented socket may also be used.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will choose the type of prosthesis that best meets your needs.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Procedure

The surgical procedure takes a few hours. Your orthopaedic surgeon will remove the damaged cartilage and bone and then position new metal, plastic, or ceramic implants to restore the alignment and function of your hip.

After surgery, you will be moved to the recovery room where you will remain for several hours while your recovery from anesthesia is monitored. After you wake up, you will be taken to your hospital room.

Your Stay in the Hospital

You will most likely stay in the hospital for a few days. To protect your hip during early recovery, a positioning splint, such as a foam pillow placed between your legs, may be used.

Pain Management

After surgery, you will feel some pain. This is a natural part of the healing process. Your doctor and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover from surgery faster.

Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery. Many types of medicines are available to help manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Your doctor may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose has become a critical public health issue in the U.S. It is important to use opioids only as directed by your doctor. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your surgery.

Physical Therapy

Home Health – Respiratory Therapy

Walking and light activity are important to your recovery. Most patients who undergo total hip replacement begin standing and walking with the help of a walking support and a physical therapist the day after surgery. In some cases, patients begin standing and walking on the actual day of surgery. The physical therapist will teach you specific exercises to strengthen your hip and restore movement for walking and other normal daily activities.

Preventing Pneumonia

It is common for patients to have shallow breathing in the early postoperative period. This is usually due to the effects of anesthesia, pain medications, and increased time spent in bed. This shallow breathing can lead to a partial collapse of the lungs (termed “atelectasis”) which can make patients susceptible to pneumonia. To help prevent this, it is important to take frequent deep breaths. Your nurse may provide a simple breathing apparatus called a spirometer to encourage you to take deep breaths.

Recovery

The success of your surgery will depend in large measure on how well you follow your orthopaedic surgeon’s instructions regarding home care during the first few weeks after surgery.

Wound Care

You may have stitches or staples running along your wound or a suture beneath your skin. The stitches or staples will be removed approximately 2 weeks after surgery.

Avoid getting the wound wet until it has thoroughly sealed and dried. You may continue to bandage the wound to prevent irritation from clothing or support stockings.

Diet

Some loss of appetite is common for several weeks after surgery. A balanced diet, often with an iron supplement, is important to promote proper tissue healing and restore muscle strength. Be sure to drink plenty of fluids.

Activity

Mature woman in physical therapy

Exercise is a critical component of home care, particularly during the first few weeks after surgery. You should be able to resume most normal light activities of daily living within 3 to 6 weeks following surgery. Some discomfort with activity and at night is common for several weeks.

Your activity program should include:

- A graduated walking program to slowly increase your mobility, initially in your home and later outside

- Resuming other normal household activities, such as sitting, standing, and climbing stairs

- Specific exercises several times a day to restore movement and strengthen your hip. You probably will be able to perform the exercises without help, but you may have a physical therapist help you at home or in a therapy center the first few weeks after surgery

Possible Complications of Surgery

The complication rate following hip replacement surgery is low. Serious complications, such as joint infection, occur in less than 2% of patients. Major medical complications, such as heart attack or stroke, occur even less frequently. However, chronic illnesses may increase the potential for complications. Although uncommon, when these complications occur they can prolong or limit full recovery.

Infection

Infection may occur superficially in the wound or deep around the prosthesis. It may happen while in the hospital or after you go home. It may even occur years later.

Minor infections of the wound are generally treated with antibiotics. Major or deep infections may require more surgery and removal of the prosthesis. Any infection in your body can spread to your joint replacement.

Blood Clots

Blood clots in the leg veins or pelvis are one of the most common complications of hip replacement surgery. These clots can be life-threatening if they break free and travel to your lungs. Your orthopaedic surgeon will outline a prevention program which may include blood thinning medications, support hose, inflatable leg coverings, ankle pump exercises, and early mobilization.

Leg-length Inequality

Sometimes after a hip replacement, one leg may feel longer or shorter than the other. Your orthopaedic surgeon will make every effort to make your leg lengths even, but may lengthen or shorten your leg slightly in order to maximize the stability and biomechanics of the hip. Some patients may feel more comfortable with a shoe lift after surgery.

Dislocation

This occurs when the ball comes out of the socket. The risk for dislocation is greatest in the first few months after surgery while the tissues are healing. Dislocation is uncommon. If the ball does come out of the socket, a closed reduction usually can put it back into place without the need for more surgery. In situations in which the hip continues to dislocate, further surgery may be necessary.

Loosening and Implant Wear

Over years, the hip prosthesis may wear out or loosen. This is most often due to everyday activity. It can also result from a biologic thinning of the bone called osteolysis. If loosening is painful, a second surgery called a revision may be necessary.

Other Complications

Nerve and blood vessel injury, bleeding, fracture, and stiffness can occur. In a small number of patients, some pain can continue or new pain can occur after surgery.

Avoiding Problems After Surgery

Recognizing the Signs of a Blood Clot

Follow your orthopaedic surgeon’s instructions carefully to reduce the risk of blood clots developing during the first several weeks of your recovery. He or she may recommend that you continue taking the blood thinning medication you started in the hospital. Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of the following warning signs.

Warning signs of blood clots. The warning signs of possible blood clot in your leg include:

- Pain in your calf and leg that is unrelated to your incision

- Tenderness or redness of your calf

- New or increasing swelling of your thigh, calf, ankle, or foot

Warning signs of pulmonary embolism. The warning signs that a blood clot has traveled to your lung include:

- Sudden shortness of breath

- Sudden onset of chest pain

- Localized chest pain with coughing

Preventing Infection

A common cause of infection following hip replacement surgery is from bacteria that enter the bloodstream during dental procedures, urinary tract infections, or skin infections.

Following surgery, patients with certain risk factors may need to take antibiotics prior to dental work, including dental cleanings, or before any surgical procedure that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. Your orthopaedic surgeon will discuss with you whether taking preventive antibiotics before dental procedures is needed in your situation.

Warning signs of infection. Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of the following signs of a possible hip replacement infection:

- Persistent fever (higher than 100°F orally)

- Shaking chills

- Increasing redness, tenderness, or swelling of the hip wound

- Drainage from the hip wound

- Increasing hip pain with both activity and rest

Avoiding Falls

A fall during the first few weeks after surgery can damage your new hip and may result in a need for more surgery. Stairs are a particular hazard until your hip is strong and mobile. You should use a cane, crutches, a walker, or handrails or have someone help you until you improve your balance, flexibility, and strength.

Your orthopaedic surgeon and physical therapist will help you decide which assistive aides will be required following surgery, and when those aides can safely be discontinued.

Other Precautions

To assure proper recovery and prevent dislocation of the prosthesis, you may be asked to take special precautions when sitting, bending, or sleeping — usually for the first 6 weeks after surgery. These precautions will vary from patient to patient, depending on the surgical approach your surgeon used to perform your hip replacement.

Prior to discharge from the hospital, your surgeon and physical therapist will provide you with any specific precautions you should follow.

Outcomes

How Your New Hip Is Different

You may feel some numbness in the skin around your incision. You also may feel some stiffness, particularly with excessive bending. These differences often diminish with time, and most patients find these are minor compared with the pain and limited function they experienced prior to surgery.

Your new hip may activate metal detectors required for security in airports and some buildings. Tell the security agent about your hip replacement if the alarm is activated. You may ask your orthopaedic surgeon for a card confirming that you have an artificial hip.

Protecting Your Hip Replacement

There are many things you can do to protect your hip replacement and extend the life of your hip implant.

- Participate in a regular light exercise program to maintain proper strength and mobility of your new hip.

- Take special precautions to avoid falls and injuries. If you break a bone in your leg, you may require more surgery.

- Make sure your dentist knows that you have a hip replacement. Talk with your orthopaedic surgeon about whether you need to take antibiotics prior to dental procedures.

- See your orthopaedic surgeon periodically for routine follow-up examinations and x-rays, even if your hip replacement seems to be doing fine.

Arthritis literally means “inflammation of a joint.” In some forms of arthritis, such as osteoarthritis, the inflammation arises because the smooth covering (articular cartilage) on the ends of bones become damaged or worn. Osteoarthritis is usually found in one, usually weightbearing, joint.

In other forms of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, the joint lining becomes inflamed as part of a disease process that affects the entire body. Some other types of arthritis are: seronegative spondyloarthropathies, crytalline deposition diseases, and septic arthritis.

Arthritis is a major cause of lost work time and serious disability for many people. Although arthritis is mainly a disease of adults, children may also have it.

Anatomy

Arthritis is a disease of the joint. A joint is where the ends of two or more bones meet. The knee joint, for example, is formed between the bones of the lower leg (the tibia and the fibula) and the thighbone (the femur). The hip joint is where the top of the thighbone (femoral head) meets a concave portion of the pelvis (the acetabulum).

A smooth tissue of cartilage covers the ends of bones in a joint. Cartilage cushions the bone and allows the joint to move easily without the friction that would come with bone-on-bone contact. A joint is enclosed by a fibrous envelope, called the synovium, which produces a fluid that also helps to reduce friction and wear in a joint. Ligaments connect the bones and keep the joint stable. Muscles and tendons power the joint and enable it to move.

Cause

There are two major categories of arthritis.

The first type is caused by wear and tear on the articular cartilage (osteoarthritis) through the natural aging process, through constant use, or through trauma (post-traumatic arthritis).

The second type is caused by one of a number of inflammatory processes.

Regardless of whether the cause is from injury, normal wear and tear, or disease, the joint becomes inflamed, causing swelling, pain and stiffness. This is usually temporary. Inflammation is one of the body’s normal reactions to injury or disease. In arthritic joints, however, inflammation may cause long-lasting or permanent disability.

Natural History

Osteoarthritis

The most common type of arthritis is osteoarthritis. It results from overuse, trauma, or the degeneration of the joint cartilage that takes place with age. Osteoarthritis is often more painful in joints that bear weight, such as the knee, hip, and spine, rather than in the wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints. However, joints that are used extensively in work or sports or joints that have been damaged from fractures or other injuries may show signs of osteoarthritis. Other disorders that injure or overload the articular cartilage may lead to osteoarthritis.

In osteoarthritis, the cartilage covering the bone ends gradually wears away. In many cases, bone growths called “spurs” develop at the edges of osteoarthritic joints. The bone can become hard and firm (sclerosis). The joint becomes inflamed, causing pain and swelling. Continued use of the joint

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a long-lasting disease. It is estimated that 1% of the population throughout the world have rheumatoid arthritis. Women are three times more likely than men to have rheumatoid arthritis. The development of rheumatoid arthritis slows with age.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects many parts of the body, but mainly the joints. The body’s immune system, which normally protects the body, begins to produce substances that attack the body. In rheumatoid arthritis, the joint lining swells, invading surrounding tissues. Chemical substances are produced that attack and destroy the joint surface.

Rheumatoid arthritis may affect both large and small joints in the body and also the spine. Swelling, pain, and stiffness usually develop, even when the joint is not used. In some circumstances, juvenile arthritis may cause similar symptoms in children.

Diagnosis

Arthritis is diagnosed through a careful evaluation of symptoms and a physical examination. X-rays are important to show the extent of any damage to the joint. Blood tests and other laboratory tests may help to determine the type of arthritis. Some of the findings of arthritis include:

- Weakness (atrophy) in the muscles

- Tenderness to touch

- Limited ability to move the joint passively (with assistance) and actively (without assistance).

- Signs that other joints are painful or swollen (an indication of rheumatoid arthritis)

- A grating feeling or sound (crepitus) with movement

- Pain when pressure is placed on the joint or the joint is moved

Medications

Over-the-counter medications can be used to control pain and inflammation in the joints. These medications, called anti-inflammatory drugs, include aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen. Acetaminophen can be effective in controlling pain.

Prescription medications also are available. A physician will choose a medication by taking into account the type of arthritis, its severity, and the patient’s general physical health. Patients with ulcers, asthma, kidney, or liver disease, for example, may not be able to safely take anti-inflammatory medications.

Injections of cortisone into the joint may temporarily help to relieve pain and swelling. It is important to know that repeated, frequent injections into the same joint can damage it, causing undesirable side effects.

Viscosupplementation or injection of hyaluronic acid preparations can also be helpful in lubricating the joint. This is typically perfomed in the knee.

Exercise and Therapy

Canes, crutches, walkers, or splints may help relieve the stress and strain on arthritic joints. Learning methods of performing daily activities that are the less stressful to painful joints also may be helpful.

Certain exercises and physical therapy may be used to decrease stiffness and to strengthen the weakened muscles around the joint.

Surgery

In general, an orthopaedic surgeon will perform surgery for arthritis when other methods of nonsurgical treatment have failed to relieve pain and other symptoms. When deciding on the type of surgery, the physician and patient will take into account the type of arthritis, its severity, and the patient’s physical condition.

There are a number of surgical procedures. These include:

- Removing the diseased or damaged joint lining

- Realignment of the joints

- Fusing the ends of the bones in the joint together, to prevent joint motion and relieve joint pain

- Replacing the entire joint (total joint replacement)

Long-Term Management

In most cases, persons with arthritis can continue to perform normal activities of daily living. Exercise programs, anti-inflammatory drugs, and weight reduction for obese persons are common measures to reduce pain, stiffness, and improve function.

In persons with severe cases of arthritis, orthopaedic surgery can often provide dramatic pain relief and restore lost joint function.

Some types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are often treated by a team of health care professionals. These professionals may include rheumatologists, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and orthopaedic surgeons.

Research

At present, most types of arthritis cannot be cured. Researchers continue to make progress in finding the underlying causes for the major types of arthritis. In the meantime, orthopaedic surgeons, working with other physicians and scientists, have developed many effective treatments for arthritis.

Hip Fractures

A hip fracture is a break in the upper quarter of the femur (thigh) bone. The extent of the break depends on the forces that are involved. The type of surgery used to treat a hip fracture is primarily based on the bones and soft tissues affected or on the level of the fracture.

Anatomy

The “hip” is a ball-and-socket joint. It allows the upper leg to bend and rotate at the pelvis. An injury to the socket, or acetabulum, itself is not considered a “hip fracture.” Management of fractures to the socket is a completely different consideration.

Causes

Hip fractures most commonly occur from a fall or from a direct blow to the side of the hip. Some medical conditions such as osteoporosis, cancer, or stress injuries can weaken the bone and make the hip more susceptible to breaking. In severe cases, it is possible for the hip to break with the patient merely standing on the leg and twisting.

Symptoms

The patient with a hip fracture will have pain over the outer upper thigh or in the groin. There will be significant discomfort with any attempt to flex or rotate the hip.

If the bone has been weakened by disease (such as a stress injury or cancer), the patient may notice aching in the groin or thigh area for a period of time before the break. If the bone is completely broken, the leg may appear to be shorter than the noninjured leg. The patient will often hold the injured leg in a still position with the foot and knee turned outward (external rotation).

Doctor Examination

Imaging

The diagnosis of a hip fracture is generally made by an X-ray of the hip and femur.

In some cases, if the patient falls and complains of hip pain, an incomplete fracture may not be seen on a regular X-ray. In that case, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be recommended. The MRI scan will usually show a hidden fracture.

If the patient is unable to have an MRI scan because of an associated medical condition, computed tomography (CT) may be obtained instead. Computed tomography, however, is not as sensitive as MRI for seeing hidden hip fractures.

Types of Fractures

In general, there are three different types of hip fractures. The type of fracture depends on what area of the upper femur is involved.

Intracapsular Fracture

These fractures occur at the level of the neck and the head of the femur, and are generally within the capsule. The capsule is the soft-tissue envelope that contains the lubricating and nourishing fluid of the hip joint itself.

Intertrochanteric Fracture

This fracture occurs between the neck of the femur and a lower bony prominence called the lesser trochanter. The lesser trochanter is an attachment point for one of the major muscles of the hip. Intertrochanteric fractures generally cross in the area between the lesser trochanter and the greater trochanter. The greater trochanter is the bump you can feel under the skin on the outside of the hip. It acts as another muscle attachment point.

Subtrochanteric Fracture

This fracture occurs below the lesser trochanter, in a region that is between the lesser trochanter and an area approximately 2 1/2 inches below .

In more complicated cases, the amount of breakage of the bone can involve more than one of these zones. This is taken into consideration when surgical repair is considered.

Treatment

Considerations

Once the diagnosis of the hip fracture has been made, the patient’s overall health and medical condition will be evaluated. In very rare cases, the patient may be so ill that surgery would not be recommended. In these cases, the patient’s overall comfort and level of pain must be weighed against the risks of anesthesia and surgery.

Most surgeons agree that patients do better if they are operated on fairly quickly. It is, however, important to insure patients’ safety and maximize their overall medical health before surgery. This may mean taking time to do cardiac and other diagnostic studies.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Patients who might be considered for nonsurgical treatment include those who are too ill to undergo any form of anesthesia and people who were unable to walk before their injury and may have been confined to a bed or a wheelchair.

Certain types of fractures may be considered stable enough to be managed with nonsurgical treatment. Because there is some risk that these “stable” fractures may instead prove unstable and displace (change position), the doctor will need to follow with periodic X-rays of the area. If patients are confined to bed rest as part of the management for these fractures, they will need to be closely monitored for complications that can occur from prolonged immobilization. These include infections, bed sores, pneumonia, the formation of blood clots, and nutritional wasting.

Surgical Treatment

Before Surgery

Anesthesia for surgery could be either general anesthesia with a breathing tube or spinal anesthesia. In very rare circumstances, where only a few screws are planned for fixation, local anesthesia with heavy sedation can be considered. All patients will receive antibiotics during surgery and for the 24-hours afterward.

Appropriate blood tests, chest X-rays, electrocardiograms, and urine samples will be obtained before surgery. Many elderly patients may have undiagnosed urinary tract infections that could lead to an infection of the hip after surgery.

The surgeon’s decision as to how to best fix a fracture will be based on the area of the hip that is broken and the surgeon’s familiarity with the different systems that are available to manage these injuries.

Intracapsular Fracture

If the head of the femur (“ball”) alone is broken, management will be aimed at fixing the cartilage on the ball that has been injured or displaced. Frequently with these injuries, the socket, or acetabulum, may also be broken. The surgeon will need to take this into consideration as well.

These injuries may be approached either from either the front or back of the hip. In some cases, both approaches are required in order to clearly see and fix the injured bone.

For true intracapsular hip fractures, the surgeon may decide either to fix the fracture with individual screws (percutaneous pinning) or a single larger screw that slides within the barrel of a plate. This compression hip screw will allow the fracture to become more stable by having the broken area impact on itself. Occasionally, a secondary screw may be added for stability.

If the intracapsular hip fracture is displaced in a younger patient, a surgical attempt will be made to reduce, or realign, the fracture through a larger incision. The fracture will be held together with either individual screws or with the larger compression hip screw.

In these cases, the blood supply to the ball, or head of the femur, may have been damaged at the time of injury (avascular necrosis). Even though the fracture is realigned and fixed into place, the cartilage and underlying supporting bone may not receive adequate blood. Over a period of time, this may cause the femoral head to flatten out. When this occurs, the joint surface becomes irregular. Ultimately, the hip joint may develop a painful arthritis, despite the surgical repair.

In the older patient, the chance that the head of the femur is damaged in this way is higher. It is generally felt that for these displaced fractures, patients will do better if some of the components of the hip are replaced. In some cases, this can mean a replacement of the ball, or head of the femur (hemiarthroplasty). In other cases, this can mean the replacement of both the ball and socket, or head of the femur and acetabulum (total hip replacement).