The following article provides in-depth information about treatment for anterior cruciate ligament injuries. The general article, Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries, provides a good introduction to the topic and is recommended reading prior to this article.

The information that follows includes the details of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) anatomy and the pathophysiology of an ACL tear, treatment options for ACL injuries along with a description of ACL surgical techniques and rehabilitation, potential complications, and outcomes. The information is intended to assist the patient in making the best-informed decision possible regarding the management of ACL injury.

Anatomy

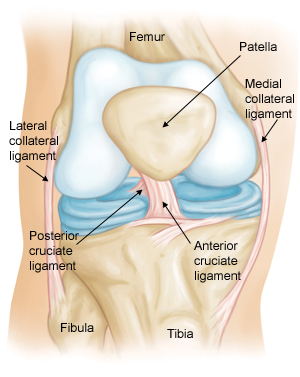

The bone structure of the knee joint is formed by the femur, the tibia, and the patella. The ACL is one of the four main ligaments within the knee that connect the femur to the tibia.

The knee is essentially a hinged joint that is held together by the medial collateral (MCL), lateral collateral (LCL), anterior cruciate (ACL) and posterior cruciate (PCL) ligaments. The ACL runs diagonally in the middle of the knee, preventing the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, as well as providing rotational stability to the knee.

The weight-bearing surface of the knee is covered by a layer of articular cartilage. On either side of the joint, between the cartilage surfaces of the femur and tibia, are the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. The menisci act as shock absorbers and work with the cartilage to reduce the stresses between the tibia and the femur.

Description

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most commonly injured ligaments of the knee. The incidence of ACL injuries is currently estimated at approximately 200,000 annually, with 100,000 ACL reconstructions performed each year.1, 2 In general, the incidence of ACL injury is higher in people who participate in high-risk sports, such as basketball, football, skiing, and soccer.3, 4, 5

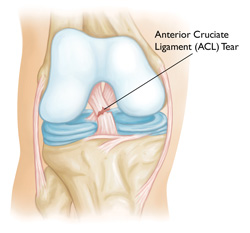

Approximately 50 percent of ACL injuries occur in combination with damage to the meniscus, articular cartilage, or other ligaments. Additionally, patients may have bruises of the bone beneath the cartilage surface. These may be seen on a magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) scan and may indicate injury to the overlying articular cartilage.

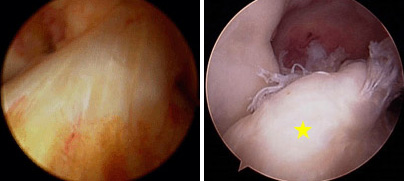

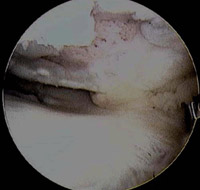

(Left) Arthroscopic picture of the normal ACL. (Right) Arthroscopic picture of torn ACL [yellow star].

Cause

It is estimated that 70 percent of ACL injuries occur through non-contact mechanisms while 30 percent result from direct contact with another player or object.4

The mechanism of injury is often associated with deceleration coupled with cutting, pivoting or sidestepping maneuvers, awkward landings or “out of control” play.

Several studies have shown that female athletes have a higher incidence of ACL injury than male athletes in certain sports.3, 10 It has been proposed that this is due to differences in physical conditioning, muscular strength, and neuromuscular control.

Other hypothesized causes of this gender-related difference in ACL injury rates include pelvis and lower extremity (leg) alignment, increased ligamentous laxity, and the effects of estrogen on ligament properties.

Immediately after the injury, patients usually experience pain and swelling and the knee feels unstable. Within a few hours after a new ACL injury, patients often have a large amount of knee swelling, a loss of full range of motion, pain or tenderness

along the joint line and discomfort while walking.

Doctor Examination

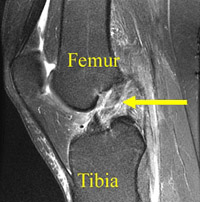

When a patient with an ACL injury is initially seen for evaluation in the clinic, the doctor may order X-rays to look for any possible fractures. He or she may also order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to evaluate the ACL and to check for evidence of injury to other knee ligaments, meniscus cartilage, or articular cartilage.

In addition to performing special tests for identifying meniscus tears and injury to other ligaments of the knee, the physician will often perform the Lachman’s test to see if the ACL is intact.

<iframe width=”520″ height=”360″ class=”youtube-embed” src=”http://www.youtube.com/embed/j6yuI59_yMM?wmode=opaque&rel=0″ frameborder=”0″ wmode=”opaque” allowfullscreen=””></iframe>

If the ACL is torn, the examiner will feel increased forward (upward or anterior) movement of the tibia in relation to the femur (especially when compared to the normal leg) and a soft, mushy endpoint (because the ACL is torn) when this movement ends.

Another test for ACL injury is the pivot shift test. In this test, , the tibia will start forward when the knee is fully straight and then will shift back into the correct position in relation to the femur when the knee is bent past 30 degrees.

<iframe width=”520″ height=”360″ class=”youtube-embed” src=”http://www.youtube.com/embed/kDBCSNZX6w8?wmode=opaque&rel=0″ frameborder=”0″ wmode=”opaque” allowfullscreen=””></iframe>

Natural History

The natural history of an ACL injury without surgical intervention varies from patient to patient and depends on the patient’s activity level, degree of injury and instability symptoms.

The prognosis for a partially torn ACL is often favorable, with the recovery and rehabilitation period usually at least three months. However, some patients with partial ACL tears may still have instability symptoms. Close clinical follow-up and a complete course of physical therapy helps identify those patients with unstable knees due to partial ACL tears.

Complete ACL ruptures have a much less favorable outcome. After a complete ACL tear, some patients are unable to participate in cutting or pivoting-type sports, while others have instability during even normal activities, such as walking. There are some rare individuals who can participate in sports without any symptoms of instability. This variability is related to the severity of the original knee injury, as well as the physical demands of the patient.

Arthroscopic picture of torn medial meniscus in chronically ACL-deficient knee. In this case, the torn meniscus is pushed forward [yellow star] and locked in front of the knee [called a “bucket handle” meniscus tear], so the patient could not straighten out the leg.

About half of ACL injuries occur in combination with damage to the meniscus, articular cartilage or other ligaments. Secondary damage may occur in patients who have repeated episodes of instability due to ACL injury. With chronic instability, up to 90 percent of patients will have meniscus damage when reassessed 10 or more years after the initial injury. Similarly, the prevalence of articular cartilage lesions increases up to 70 percent in patients who have a 10-year-old ACL deficiency.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In nonsurgical treatment, progressive physical therapy and rehabilitation can restore the knee to a condition close to its pre-injury state and educate the patient on how to prevent instability.37, 38 This may be supplemented with the use of a hinged knee brace. However, many people who choose not to have surgery may experience secondary injury to the knee due to repetitive instability episodes.

Surgical treatment is usually advised in dealing with combined injuries (ACL tears in combination with other injuries in the knee). However, deciding against surgery is reasonable for select patients. Nonsurgical management of isolated ACL tears is likely to be successful or may be indicated in patients:

With partial tears and no instability symptoms39

With complete tears and no symptoms of knee instability during low-demand sports who are willing to give up high-demand sports

Who do light manual work or live sedentary lifestyles

Whose growth plates are still open (children)

Surgical Treatment

ACL tears are not usually repaired using suture to sew it back together, because repaired ACLs have generally been shown to fail over time.31, 33, 34, 35, 36 Therefore, the torn ACL is generally replaced by a substitute graft made of tendon.

Animation courtesy Visual Health Solutions, Inc.

The grafts commonly used to replace the ACL include:

Patellar tendon autograft (autograft comes from the patient)

Hamstring tendon autograft

Quadriceps tendon autograft

Allograft (taken from a cadaver) patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, semitendinosus, gracilis, or posterior tibialis tendon

Patients treated with surgical reconstruction of the ACL have long-term success rates of 82 percent to 95 percent. Recurrent instability and graft failure are seen in approximately 8 percent of patients.

The goal of the ACL reconstruction surgery is to prevent instability and restore the function of the torn ligament, creating a stable knee. This allows the patient to return to sports. There are certain factors that the patient must consider when deciding

for or against ACL surgery.

Patient Considerations

Active adult patients involved in sports or jobs that require pivoting, turning or hard-cutting as well as heavy manual work are encouraged to consider surgical treatment.This includes older patients who have previously been excluded from consideration for ACL surgery. Activity, not age, should determine if surgical intervention should be considered.

In young children or adolescents with ACL tears, early ACL reconstruction creates a possible risk of growth plate injury, leading to bone growth problems. The surgeon can delay ACL surgery until the child is closer to skeletal maturity or the surgeon may modify the ACL surgery technique to decrease the risk of growth plate injury.

A patient with a torn ACL and significant functional instability has a high risk of developing secondary knee damage and should therefore consider ACL reconstruction.

It is common to see ACL injuries combined with damage to the menisci (50 percent), articular cartilage (30 percent), collateral ligaments (30 percent), joint capsule, or a combination of the above. The “unhappy triad,” frequently seen in football players and skiers, consists of injuries to the ACL, the MCL, and the medial meniscus.

In cases of combined injuries, surgical treatment may be warranted and generally produces better outcomes. As many as 50 percent of meniscus tears may be repairable and may heal better if the repair is done in combination with the ACL reconstruction.

Surgical Choices

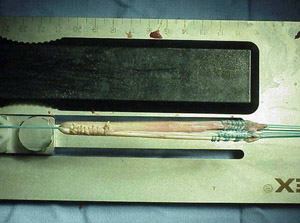

Patellar tendon autograft prepared for ACL reconstruction.

Patellar tendon autograft. The middle third of the patellar tendon of the patient, along with a bone plug from the shin and the kneecap is used in the patellar tendon autograft. Occasionally referred to by some surgeons as the “gold standard” for ACL reconstruction, it is often recommended for high-demand athletes and patients whose jobs do not require a significant amount of kneeling.57

In studies comparing outcomes of patellar tendon and hamstring autograft ACL reconstruction, the rate of graft failure was lower in the patellar tendon group (1.9 percent versus 4.9 percent).58 In addition, most studies show equal or better outcomes in terms of postoperative tests for knee laxity (Lachman’s, anterior drawer and instrumented tests) when this graft is compared to others. However, patellar tendon autografts have a greater incidence of postoperative patellofemoral pain (pain

behind the kneecap) complaints and other problems.58, 59

The pitfalls of the patellar tendon autograft are:

Postoperative pain behind the kneecap

Pain with kneeling

Slightly increased risk of postoperative stiffness

Low risk of patella fracture

Hamstring tendon autograft.

The semitendinosus hamstring tendon on the inner side of the knee is used in creating the hamstring tendon autograft for ACL reconstruction. Some surgeons use an additional tendon, the gracilis, which is attached below the knee in the same area. This creates a two- or four-strand tendon graft. Hamstring graft proponents claim there are fewer problems associated with harvesting of the graft compared to the patellar tendon autograft including:

Fewer problems with anterior knee pain or kneecap pain after surgery

Less postoperative stiffness problems

Smaller incision

Faster recovery

Hamstring tendon autograft prepared for ACL reconstruction.

The graft function may be limited by the strength and type of fixation in the bone tunnels, as the graft does not have bone plugs.There have been conflicting results in research studies as to whether hamstring grafts are slightly more susceptible to graft elongation (stretching), which may lead to increased laxity during objective testing.Recently, some studies have demonstrated decreased hamstring strength in patients after surgery.

There are some indications that patients who have intrinsic ligamentous laxity and knee hyperextension of 10 degrees or more may have increased risk of postoperative hamstring graft laxity on clinical exam. Therefore, some clinicians recommend the use of patellar tendon autografts in these hypermobile patients.

Additionally, since the medial hamstrings often provide dynamic support against valgus stress and instability, some surgeons feel that chronic or residual medial collateral ligament laxity (grade 2 or more) at the time of ACL reconstruction may be a contra-indication for use of the patient’s own semitendinosus and gracilis tendons as an ACL graft.

Quadriceps tendon autograft.

Quadriceps tendon autograft prepared for ACL reconstruction.

The quadriceps tendon autograft is often used for patients who have already failed ACL reconstruction. The middle third of the patient’s quadriceps tendon and a bone plug from the upper end of the knee cap are used. This yields a larger graft for taller and heavier patients. Because there is a bone plug on one side only, the fixation is not as solid as for the patellar tendon graft. There is a high association with postoperative anterior knee pain and a low risk of patella fracture. Patients may find the incision is not cosmetically appealing.

Allografts. Allografts are grafts taken from cadavers and are becoming increasingly popular. These grafts are also used for patients who have failed ACL reconstruction before and in surgery to repair or reconstruct more than one knee ligament. Advantages of using allograft tissue include elimination of pain caused by obtaining the graft from the patient, decreased surgery time and smaller incisions. The patellar tendon allograft allows for strong bony fixation in the tibial and femoral bone tunnels with screws.

However, allografts are associated with a risk of infection, including viral transmission (HIV and Hepatitis C), despite careful screening and processing.Several deaths linked to bacterial infection from allograft tissue (due to improper procurement and sterilization techniques) have led to improvements in allograft tissue testing and processing techniques.There have also been conflicting results in research studies as to whether allografts are slightly more susceptible to graft elongation (stretching), which may lead to increased laxity during testing.

Recently published literature may point to a higher failure rate with the use of allografts for ACL reconstruction. Failure rates ranging from 23% to 34.4% have been reported in young, active patients returning to high-demand sporting activities after ACL reconstruction with allografts. This is compared to autograft failure rates ranging from 5% to 10%.

The reason for this higher failure rate is unclear. It could be due to graft material properties (sterilization processes used, graft donor age, storage of the graft). It could possibly be due to an ill-advised earlier return to sport by the athlete because of a faster perceived physiologic recovery, when the graft is not biologically ready to be loaded and stressed during sporting activities. Further research in this area is indicated and is ongoing.

Surgical Procedure

Before any surgical treatment, the patient is usually sent to physical therapy. Patients who have a stiff, swollen knee lacking full range of motion at the time of ACL surgery may have significant problems regaining motion after surgery. It usually takes three or more weeks from the time of injury to achieve full range of motion. It is also recommended that some ligament injuries be braced and allowed to heal prior to ACL surgery.

The patient, the surgeon, and the anesthesiologist select the anesthesia used for surgery. Patients may benefit from an anesthetic block of the nerves of the leg to decrease postoperative pain.

Passage of patellar tendon graft into tibial tunnel of knee.

The surgery usually begins with an examination of the patient’s knee while the patient is relaxed due the effects of anesthesia. This final examination is used to verify that the ACL is torn and also to check for looseness of other knee ligaments that may need to be repaired during surgery or addressed postoperatively.

If the physical exam strongly suggests the ACL is torn, the selected tendon is harvested (for an autograft) or thawed (for an allograft) and the graft is prepared to the correct size for the patient.

After the graft has been prepared, the surgeon places an arthroscope into the joint. Small (one-centimeter) incisions called portals are made in the front of the knee to insert the arthroscope and instruments and the surgeon examines the condition of the knee. Meniscus and cartilage injuries are trimmed or repaired and the torn ACL stump is then removed.

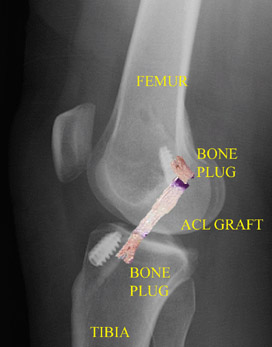

Post-operative X-ray after ACL patellar tendon reconstruction (with picture of graft superimposed) shows graft position and bone plugs fixation with metal interference screws.

In the most common ACL reconstruction technique, bone tunnels are drilled into the tibia and the femur to place the ACL graft in almost the same position as the torn ACL. A long needle is then passed through the tunnel of the tibia, up through the femoral tunnel, and then out through the skin of the thigh. The sutures of the graft are placed through the eye of the needle and the graft is pulled into position up through the tibial tunnel and then up into the femoral tunnel. The graft is held under tension as it is fixed in place using interference screws, spiked washers, posts, or staples. The devices used to hold the graft in place are generally not removed.

Variations on this surgical technique include the “two-incision,” “over-the-top,” and “double-bundle” types of ACL reconstructions, which may be used because of the preference of the surgeon or special circumstances (revision ACL reconstruction, open growth plates).

Before the surgery is complete, the surgeon will probe the graft to make sure it has good tension, verify that the knee has full range of motion and perform tests such as the Lachman’s test to assess graft stability. The skin is closed and dressings (and perhaps a postoperative brace and cold therapy device, depending on surgeon preference) are applied. The patient will usually go home on the same day of the surgery.

Arthroscopic view of ACL graft [yellow star] in position.

Pain Management

After surgery, you will feel some pain. This is a natural part of the healing process. Your doctor and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover from surgery faster.

Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery. Many types of medicines are available to help manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Your doctor may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose has become a critical public health issue in the U.S. It is important to use opioids only as directed by your doctor. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your surgery.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is a crucial part of successful ACL surgery, with exercises beginning immediately after the surgery. Much of the success of ACL reconstructive surgery depends on the patient’s dedication to rigorous physical therapy. With new surgical techniques and stronger graft fixation, current physical therapy uses an accelerated course of rehabilitation.

Postoperative Course. In the first 10 to 14 days after surgery, the wound is kept clean and dry, and early emphasis is placed on regaining the ability to fully straighten the knee and restore quadriceps control.

The knee is iced regularly to reduce swelling and pain. The surgeon may dictate the use of a postoperative brace and the use of a machine to move the knee through its range of motion.Weight-bearing status (use of crutches to keep some or all of the patient’s weight off of the surgical leg) is also determined by physician preference, as well as other injuries addressed at the time of surgery.

Rehabilitation. The goals for rehabilitation of ACL reconstruction include reducing knee swelling, maintaining mobility of the kneecap to prevent anterior knee pain problems, regaining full range of motion of the knee, as well as strengthening the quadriceps and hamstring muscles.

The patient may return to sports when there is no longer pain or swelling, when full knee range of motion has been achieved, and when muscle strength, endurance and functional use of the leg have been fully restored.

The patient’s sense of balance and control of the leg must also be restored through exercises designed to improve neuromuscular control.4 This usually takes four to six months. The use of a functional brace when returning to sports is ideally not needed after a successful ACL reconstruction, but some patients may feel a greater sense of security by wearing one.

Surgical Complications

Infection. The incidence of infection after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction has a reported range of 0.2 percent to 0.48 percent.There have also been several reported deaths linked to bacterial infection from allograft tissue due to improper procurement and sterilization techniques.

Viral transmission. Allografts specifically are associated with risk of viral transmission, including HIV and Hepatitis C, despite careful screening and processing. The chance of obtaining a bone allograft from an HIV-infected donor is calculated to be less than 1 in a million.

Bleeding, numbness. Rare risks include bleeding from acute injury to the popliteal artery (overall incidence is 0.01 percent) and weakness or paralysis of the leg or foot. It is not uncommon to have numbness of the outer part of the upper leg next to the incision, which may be temporary or permanent.

Blood clot. A blood clot in the veins of the calf or thigh is a potentially life-threatening complication. A blood clot may break off in the bloodstream and travel to the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism or to the brain, causing stroke. This risk of is reported to be approximately 0.12 percent.

Instability. Recurrent instability due to rupture or stretching of the reconstructed ligament or poor surgical technique (reported to be as low as 2.5 percent and as high as 34 percent) is possible.

Stiffness. Knee stiffness or loss of motion has been reported at between 5 percent and 25 percent.

Extensor mechanism failure. Rupture of the patellar tendon (patellar tendon autograft) or patella fracture (patellar tendon or quadriceps tendon autografts) may occur due to weakening at the site of graft harvest.

Growth plate injury. In young children or adolescents with ACL tears, early ACL reconstruction creates a possible risk of growth plate injury, leading to bone growth problems.The ACL surgery can be delayed until the child is closer to reaching skeletal maturity. Alternatively, the surgeon may be able to modify the technique of ACL reconstruction to decrease the risk of growth plate injury.

Kneecap pain. Postoperative anterior knee pain is especially common after patellar tendon autograft ACL reconstruction. The incidence of pain behind the kneecap varies between 4 percent and 56 percent in studies, whereas the incidence of kneeling pain may be as high as 42 percent after patellar tendon autograft ACL reconstruction.